It’s worked so far, hasn’t it? There have been momentary bursts of democratization in the relatively short history of the American Republic, but for the most part, the wealthiest citizens have directed the course of government with results that appeared quite satisfactory. Well, satisfactory to a segment of the population. In any case, while we celebrate the idea of a president working his way from a one-room cabin to the White House, the reality is that three out of four of those figures carved in Mount Rushmore were men of considerable means.

Just to be clear, a plutocracy is not an idea or ideology. Plutocracy is a fact; the wealthiest govern the society. Plutocracy can be relatively benign, as with the Kennedys and the Bushes, and can be positively progressive, as it was with both Roosevelts. I’ll get to Donald Trump and the Republicans’ tax plan in a moment, but it is worth noting that people of considerable wealth have made important contributions to society, from Andrew Carnegie’s endowment of libraries to Warren Buffett’s support of health care initiatives. Wealth can do a world of good, as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the less celebrated Atlantic philanthropy of Chuck Feeney demonstrate.

Wealth is just wealth. But, as the top one percent controls fifty percent of the world’s resources, their interests and proclivities have an outsized effect on the rest of the population. That’s probably not a good thing for a democratic republic, and that process now appears inevitably certain to continue to concentrate the sources of wealth in the hands of the wealthy. The question we not in that one percent ask is, do the relatively less wealthy become absolutely less wealthy as the rich get richer?

The current cultural and social differences of opinion aside, the response to that question separates liberals and conservatives. It is increasingly clear that we can study meteorology, hook up elaborate radar and imaging facilities, and still completely blow a weather forecast. Economics falls into the same category of elaborately analyzed uncertainty. The issue at the moment, however, is that economic convictions have become ideological. Trickle Down economics is not a theory; it is the conviction that reduced taxation and regulation of corporations, and capital gains brings a vibrant, healthy economy in which all boats are raised by the tide of prosperity.

As the gap between the wealthiest citizens and the rest of the pack has widened, however, certain peculiarities of economic behavior have surfaced, the most notable of which is stagnation of wages, the absence of protective labor unions, and the migration of capital. The crash of 2008, largely the result of large scale chicanery in the financial sector, left citizens homeless and robbed many of pensions and retirement funds, essentially removing a safety net for most working Americans. Six years after the end of the recession, the bottom 99% have regained about 60% of what they had before the crash. In that same period of time, incomes for the 1% jumped 37%.

The income gap is, for the most part, an invisible reality. The 99% rarely see or meet those in the top 1%. Where would, how could that happen? That separation hardly registers in the daily life of most Americans. What does register, however, is the disproportionate influence that 1% has on American political policy.

It isn’t easy to keep track of the players in that game. Some, like the Koch brothers, seem to have a hand in virtually every institutional decision; others, like Robert Mercer, who has donated more than thirty million dollars to political causes, and his daughter Rebekah, now head of the Mercer Family Foundation, emerged as among the most influential forces in the recent presidential election. Whose hand is on what campaign? Well, could be any of those with clout. Real clout. There are, after all, 4.8 million millionaires in the United States but a mere 540 billionaires, 169 of which had holdings too unsubstantial to make the Forbes list of richest Americans. That group of 540, you’ll be pleased to know, did have a combined net worth of almost 2.4 trillion dollars.

So, what’s the problem?

Big government with all its restriction and regulation is inconvenient in the operation of finance at that level. If the operating principle of capital acquisition is the acquisition of capital, nothing is more pesky than taxation. Taxation, however, seems to be the mechanism by which the operational needs of a nation are secured. The transfer of wealth does not happen spontaneously, and the day-to-day needs of the 99%, education, clean water, healthcare, a protected environment, highways, and a safety net for older and under-employed citizens pretty much depend on funds secured by the business of the nation.

Hmmmm. That does seem to be a problem.

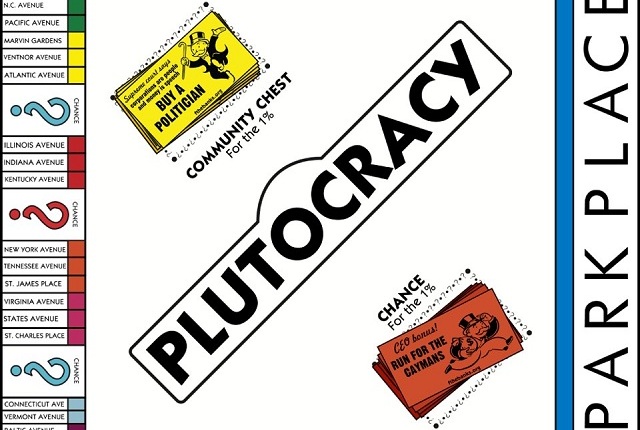

Back in 1975, acerbic author and political commentator Gore Vidal opined, “There is only one Party in the United States, the Property Party … and it has two right wings: Republican and Democrat.” A lot has happened since 1975, but the basic question remains. In this United States of ours a democracy, a democratic republic, or is it a thinly disguised plutocracy in which wealth and political power are indistinguishable?

The rich are certainly getting richer. The poor? Look around you.

So often when I read your posts, I feel like you have read my mind. I really liked these last 2 enormously.

LikeLike

Peter, Thank you for this very compelling blog. Clear, balanced — I am grateful! I often devolve into hurt and anger. Not especially effective in a discussion of these realities. Mind if I borrow from you — I promise I will give credit where it is most certainly due!

LikeLike